Berhanu Nega, an Ethiopian opposition leader based in Eritrea, has confirmed that the drought which has hit the whole of the Horn has taken a terrible toll on Eritrea as well.

In a speech broadcast on his own television station he said that Eritrea experienced a complete crop failure in the Gash-Barka region last summer. Famine has only been averted by purchasing vast quantities of imported food.

Berhanu Nega – the leader of Ginbot 7 – won the 2005 election in Addis Ababa, but was not allowed to take up his post as mayor of the capital.

Below is a translation of his speech.

Starting at 17:08 he contrasts the way Ethiopia’s ruling party (the EPRDF) is coping with the drought with the Eritrean ruling party (the PFDJ). He adds the caveat that he is not here to praise Eritreans.

17:12

He says: The most amazing thing is this: now you don’t hear the Eritreans talk about this [drought]. I am not hear to talk about how good they are or anything like that but, I find this fascinating in relation to this situation.

17:18

This year there has been a 100% crop failure in Eritrea. They haven’t produced anything

17:32

The el Nino effect has been such that there is a complete drought.

17:41

The main productive region – the Gash Barka region – has produces nothing; absolutely zero harvest.

17:44

But in Eritrea you hear nothing about the drought, the hunger or the usual consequences of drought: a price hike of food etc. That discourse doesn’t exist

18:00

This struck me and I spoke to one of the leaders,

18:06

He told me ‘in July when we realise that the rain had totally failed, we bought food to feed everyone for a whole year. We have stopped everything else [to enable us to do this]

18:29

By doing this they managed to feed people and also control the market.

18:39

So you don’t hear anything about drought now

18:40

I am saying this because drought and famine are two different things. Drought is something that occurs occasionally and is natural but famine is invariably an administrative and a consequence of lack of accountability.

Background

Previously I published the information below about drought in Eritrea.

Will Eritrea’s drought turn into a silent famine?

Martin Plaut and Mirjam van Reisen

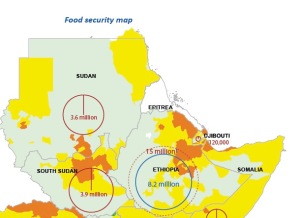

The Horn of Africa is facing its most severe drought in decades. ‘The worst drought in Ethiopia for 50 years is happening right now’, warned John Graham, Save the Children’s Country Director in Ethiopia.[1]

More than 10 million people will face severe food shortages in 2016. It is a message echoed by aid agencies and the United Nations.

The BBC Clive Myrie to report from northern Ethiopia. ‘This year the rains failed,’ he told audience from the town of Kobo.[2] ‘The UN says in one area two babies are dying every day.’

TV footage has been accompanied by urgent appeals for aid, similar to those issued during the last great famine in 1984-85.

But drought is no respecter of borders. While Ethiopia has faced up to the scale of the crisis not a single word has been issued by neighbouring Eritrea. Yet the evidence is beginning to mount up that the country is facing a similar crisis.

But drought is no respecter of borders. While Ethiopia has faced up to the scale of the crisis not a single word has been issued by neighbouring Eritrea. Yet the evidence is beginning to mount up that the country is facing a similar crisis.

This can be gleaned from a number of sources. The latest satellite imaging from the World Food Programme shows areas of the Eritrea’s highlands and western lowlands in deep orange. Here crops are somewhere between 50% and 70% below normal.

The UN humanitarian outlook report which has just been released underlines this. [3] While its main commentary provide no insight into the situation in Eritrea[4] – which is left blank on several maps – it does begin to lift the lid on what is taking place.

The report accepts that drought may be ‘affecting both cereal production and pastures in different parts of the country. According to satellite-based monitoring, significant soil moisture deficits persist in most Red Sea coastal agro-pastoral areas and are expected to negatively affect most of these livelihood systems.’ The UN describes drought as a ‘medium risk’ but says it ‘could have a strong impact,’ without elaborating on either statement.

It is the Eritrean government’s reaction to these kind of reports that explains why this silent crisis has been allowed to develop. As the UN notes starkly, unlike other countries in the region: ‘There is no official national or UN El Nino contingency plan for multi hazard in Eritrea.’[5]

The unwillingness of the Eritrean authorities to even begin discuss its predicament with any outside body lies behind the reticence of the international community to speak out.

Under President Isaias Afewerki the country has become one of the most isolated and secretive in the world. There are no independent sources of information, with the free press silenced since a government crackdown on the opposition in 2001.

International NGO’s, some of whom backed Eritreans during their 30 year fight for independence, have been excluded from the country. The authorities – claiming that Eritreans should be self-reliant – first restricted the work of NGO’s and then began taxing their activities. In May 2005, with a quarter of the population reliant on food aid, the government unveiled an NGO law which required them to pay taxes on all imports – including food and medicines.

Further restrictions were imposed on what kinds of development might be permitted. In February 2006 six Italian aid agencies were asked to leave the country and others were soon told to close down. Even UN agencies found their work curtailed, which is why few have more than skeleton operations inside Eritrea.

This explains why the response from the international community has been so hesitant. Contacts inside the country say that food is hard to come by and prices are high. Government subsidised essentials are difficult to obtain and when they are available are strictly rationed.

During a recent visit to Ethiopian refugee camps women described how they had left Eritrea after being denied government food vouchers. This was a routine reprisal – they said – after a relative fled the country to escape conscription. These stories are borne out by evidence collected by the UN Human Rights Council.[6]

This information comes mainly from the urban areas of Eritrea. What is happening to the millions in the rural areas is a closed book. But even in a good year nutrition is poor and many go hungry. Only if the drought turns to famine and the bodies start piling up are we likely to hear cries for help. By that time it may well be too late.

[1] http://www.savethechildren.org.uk/2015-12/ethiopia-drought

[2] http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-34770831

[3] http://reliefweb.int/report/world/humanitarian-outlook-horn-africa-and-great-lakes-region-october-december-2015

[4] Page 20 – 21 Food Security Map

[5] Page 29

[6] United Nations Human Rights Council (2015), Report of the detailed findings of the Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea, p. 98-98: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/CoIEritrea/Pages/ReportCoIEritrea.aspx

Update on Eritrea drought

This answer has been provided by the British government to a question in Parliament. I have added information from UN below.

Martin

Question:

To ask the Secretary of State for International Development, what assessment her Department has made of (a) the effect of the drought in the Horn of Africa on Eritrea and (b) the response of the Eritrean government and the international community to that drought. (19567)

Tabled on: 10 December 2015

Answer:

Mr Nick Hurd:

Official food security and nutrition data for Eritrea for this year has not yet been released, but the late onset of rains, relatively low volume of rainfall, and significant soil moisture deficits are likely to have had a negative impact on both farming and pastoral communities. The country and regional offices of the World Food Programme and UNICEF are monitoring the situation closely.

DFID is funding nutrition support activities in areas affected by El Nino in the Horn of Africa through UNICEF’s regional programme, which covers Eritrea

The answer was submitted on 15 Dec 2015 at 16:42.

UN update

Page 16 of the report notes that between 2011 and 2013 WFP reported that 60% of Eritreans were undernourished. At the present time 1.2 million people need food aid.

And – “Operations and the maintenance of established humanitarian systems remain a significant challenge.”

In other words, the Eritrean government refuses to allow these normal procedures to be established and maintained.