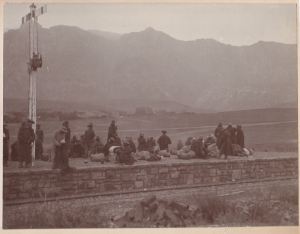

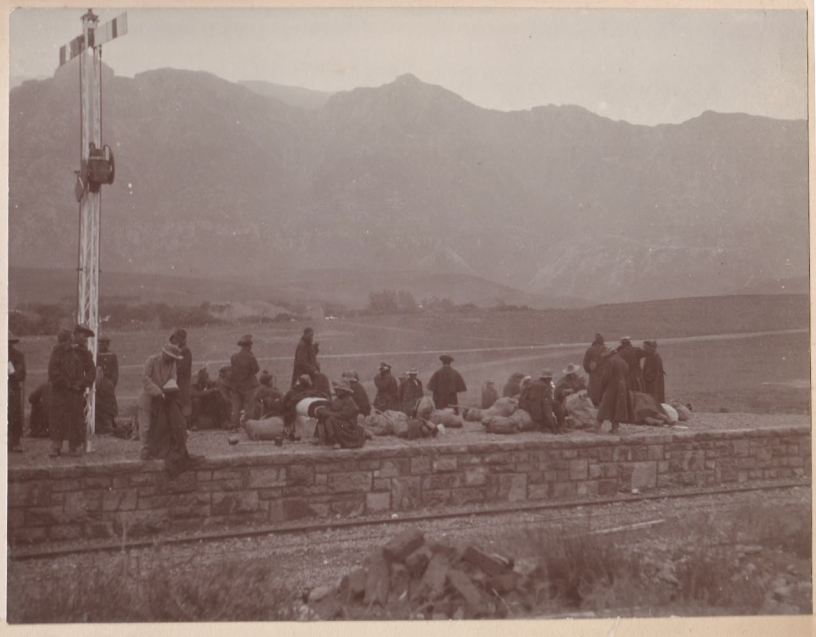

I have come across two rare photographs of groups of Africans who were involved in the Anglo-Boer war. The war was traditionally seen as a “white man’s war”, but this is now contested. These images came with this caption: “Kaffir Non-Combatants. Mule drivers etc. (Boer war 1901).

I have come across two rare photographs of groups of Africans who were involved in the Anglo-Boer war. The war was traditionally seen as a “white man’s war”, but this is now contested. These images came with this caption: “Kaffir Non-Combatants. Mule drivers etc. (Boer war 1901).

This is a story I have been working on as part of my book on South Africa between the Boer war and World War One.

Martin

A black man’s war

From the outset both sides in the conflict attempted to portray it as a ‘white man’s war’. In theory the British as well as the Afrikaners rejected the idea that Africans or even Coloureds or Indians would play in role in their dispute. The Cape government maintained that arming Africans would create an unfavourable effect on the African population; a stand endorsed by the British government.[1] This did not exclude the use of labourers or transport employees, but Africans were not meant to be armed and used in conflict.

When the going got tough, however, it was a very different story. In April-May 1900, during the siege of Mafeking, Colonel Baden Powell, who was leading the defence, ran out of troops. He had little option but to turn to Africans, who had been recruited to dig trenches and act as spies. The Colonel armed three hundred Africans; called them the ‘Black Watch’ and set them the task of manning sections of the perimeter.[2] When his opposite number, General Cronje discovered what had happened, he was furious. “It is understood that you have armed Bastards, Fingoes and Barolong against us,” he wrote in a letter to Baden-Powell. “In this you have committed an enormous act of wickedness…reconsider the matter, even if it costs you the loss of Mafeking…disarm your blacks and thereby act the part of a white man in a white man’s war.”[3]

Certainly, the black population who lived through the siege of Mafeking had – even before the war broke out – no belief that they could somehow escape the conflict. Sol Plaatje, whose diary vividly recorded life during the siege, explained how the Barolong refused to accept assurances that this would be an exclusively ‘white man’s war.’ “We remember how chief Montshiwa and his councillor Joshua Molema went round the Magistrate’s chair,” Plaatje later recalled, “and crouching behind him said:

‘Let us say, for the sake of argument, that your assurances are genuine, and that when trouble begins we hide behind your back like this, and, rifle in hand, you do all the fighting because you are white; let us say, further, that some Dutchmen appear on the scene and they outnumber and shoot you: what would be our course of action then? Are we to run home, put on skirts and hoist the white flag?’ Chief Motshegare pulled off his coat, undid his shirt front and baring his shoulder showing an old bullet scar, received in the Boer-Barolong war prior to the British occupation of Bechuanaland, he said: ‘Until you satisfy me that His Majesty’s white troops are impervious to bullets, I am going to defend my own wife and children. I have got my rifle at home and all I want is ammunition.’”[4]

In fact ‘non-whites’ had played a part in British defences from the start of the war. The Cape Mounted Rifles – a white force designed to protect the Transkei and East Griqualand was supported by a Native Affairs Department Police force of some 600 men, which contained African and white police.[5] Soon it became clear that such measures would not be sufficient. The Prime Minister of the Cape, W.P. Schreiner, who was in later years to be a staunch advocate of African rights, was, during the early years of the war resolutely opposed to any African participation. As the threat from Boer attacks into the Cape grew, his attitude changed, and he relented, allowing the Transkeian forces to”defend themselves and their districts against actual invasion.”[6] Milner, as High Commissioner wrote forcibly that this step was only to be taken as a last resort. “What I think about arming Natives is, when we have said ‘Don’t do it until absolutely necessary’ we have said all we can, without unduly interfering with the discretion of the man-on-the-spot.”[7] By December 1899 African levies were being raised by magistrates all along the borders, for their defence.

Lord Kitchener, who took over as Commander-in-Chief at the end of 1900, had fewer scruples about using black troops. At the same time, he was less than keen to advertise the fact. When the Secretary of State for War, St John Brodrick, asked for the numbers being deployed, Kitchener was less than forthcoming.[8] When pressed he finally conceded that 10,053 had been armed. They were used extensively as scouts, guides, despatch riders, sentries and guards along the vast lines of Kitchener’s blockhouses. This figures is almost certainly a gross under-estimate. A further 5,000-6,000 men – mostly Coloured – were used as town guards in the Cape alone.[9] Some estimates put the total number of Africans who fought for the British as high as 30,000.[10]

Those who were captured by the Boers were often killed. Abraham Esau, a Coloured blacksmith in the little town of Calvinia was celebrated as a martyr for his heroic resistance to a Boer attack, during which he was whipped, kicked and mutilated before finally being shot.[11] The memory of his death remained for many years. When a priest visited the area in 1986 said he found many homes in which the pictures of Queen Victoria and Edward VII still hung and there was a strong allegiance to Britain.

‘Black Boers’

If the British had, somewhat reluctantly, turned to black soldiers to bolster their army, so had the Boers. Lieutenant Charles Massey, an intelligence officer with the Grenadier Guards, accumulated “evidence of both armed and unarmed natives among our adversaries in the [Cape] colony.”[12] Boer Commandos had been observed and “all had some natives armed, and on horseback, wearing slouch hats and other Boer clothes…I have always believed what was said of the Boers and their abhorrence of blacks, but now I know better.”

Senior Boer commanders strenuously denied that this ever took place. General Jan Smuts told the strongly pro-Boer British journalist, W. T. Stead that: “The leaders of the Boers have steadfastly refused to make use of coloured assistance in the course of the present war. Offers of such assistance were courteously refused by the government of the South African Republic, who always tried to make it perfectly clear to the Natives that the war did not concern them and would not affect them so long as they remained quiet….The only instance in the whole war in which the Boers made use of armed Kaffirs happened at the siege of Mafeking when an incompetent Boer officer, without the knowledge of the Government or the Commandant-General, put a number of armed Natives into some forts.”[13]

The evidence, assiduously collected by authors like Bill Nasson, point firmly to the inaccuracy of this statement. What he describes as ‘fighting retainers’ (or agterryers, in Afrikaans) were widely deployed. Some were captured and interrogated by the British. As one British officer put it: “I talked to some of the Boer prisoners and found that there were Coloured men among the Boers, half Dutch, half Native. Also, a goodly number of Kaffirs. The Boers claimed they were only employing black men for digging, driving oxen, etc., but we know that some regularly used rifles.”[14]

Another British officer remarked on the camaraderie between the Boers and their African compatriots: “I was very surprised at their familiarity with their black comrades…they laugh, talk eat and joke with them like equals.”[15] Perhaps the exigencies of war had brought together and united bands of men who had come to rely on each other for their lives and bonds had been formed that cut across the old enmities that had divided them.

The role of these ‘black Boers’ is captured in this British ditty:[16]

‘Tommy, Tommy, watch your back

There are dusky wolves in cunning Piet’s pack

Sometimes nowhere to be seen

Sometimes up and shooting clean

They’re steathy lads, stealthy and brave

In darkness they’re awake

Duck, Duck, that bullet isn’t fake.

Black South Africans and the British victory

The death toll in the war was terrible. Some 22,000 British and colonial troops were buried in South Africa. The Boers lost around 7,000 at the front and perhaps as many as 28,000 women and children in the concentration camps.[17] But, as Thomas Pakenham points out in assessing the conflict, the most severe losses were suffered by Africans. No-one bothered to keep accurate records of the ‘black Boers’ who were swept up into the concentration camps – the farm workers and their families who had been captured during the burning of Boer farms, but recent research suggests that some 18,000 Africans perished in the camps.[18]

There is evidence the Boers executed large numbers of Africans for helping the British either as despatch riders or armed scouts. Kitchener wrote to Brodrick, the Secretary of State for war, saying that “Cold-blooded murder of natives by Boers are frequent.[19] On 10 November, 2 dead bodies of natives, with hands tied behind them, were found in mine shaft near Graylingstadt. They had been shot. Sworn evidence is being collected.”

Commandant Gideon Scheepers was found guilty of shooting 7 Africans, as well as train wrecking and floggings. He was tied to a chair and shot, despite a plea for clemency General de Wet sent to Kitchener. De Wet wrote that “the ungovernable barbarity of the natives realises itself in practice in such a manner that we felt ourselves obliged to give quarter to no native and for these reasons we gave general instructions to our Officers to have all armed natives and native spies shot.” De Wet then said that if anybody was responsible for shooting natives then it was himself and his government.

Kitchener rejected the appeal, replying that Boer officers were personally responsible for their actions: “[I am] astonished at the barbarous instructions you have given as regards the murder of natives who…have behaved in my opinion, in an exemplary manner during the war.” De Wet was then informed that Scheepers had already been executed.[20]

There is no an authoritative toll of the numbers of Africans or Coloureds who died serving either the British or the Boers in battle. This account by Canon Farmer, a British missionary in the Transvaal, will have to suffice as their memorial.[21]

“Of all who have suffered by the war, those who have endured most & will receive least sympathy, are the Natives in the country places of the Transvaal…they have welcomed British columns & when these columns have marched on they have been compelled to flee from the Boers, abandon most of their cattle & stuff & take refuge in the towns or fortified places, or be killed. I have been asking after my people & this account I get of them all…For instance, at Modderfontein, one of my strongest centres of Church work in the Transvaal, there was placed a garrison of 200 [white] men. The Natives – all of whom I knew – were there in their village: the Boers under [General Jan] Smuts, captured this post last month & when afterwards a column visited the place they found the bodies of all the Kaffirs murdered and unburied. I should be sorry to say anything that is unfair about the Boers. They look upon the Kaffirs as dogs & killing of them as hardly a crime.”

The suffering of the black community during the war was immense, but the anticipated benefits of a British victory soon evaporated. Africans had welcomed the British as they advanced through the Transvaal and Orange Free State as liberators. They believed that at last they would be treated as British subjects, equal to the Boers in the eyes of their new masters, but they misjudged the intentions of the conquering British.[22] “Expecting that an English victory would signal their liberation from oppressive conditions, throngs of workers burned their passes when Robert’s soldiers appeared on the Rand. In the countryside, African generally thought that the war had freed them from their former landlords, whose lands would fall into tenants’ possessions. British authorities soon dispelled these homes, though not without resistance on the part of Africans.”

Transvaal Africans who had moved onto deserted former Afrikaner farms, believing they could recover the land taken from them during and after the Great Trek, were soon disabused of this notion. British troops and police evicted them.[23] An African commentator wrote:

“One strong incentive reason impelled the Natives of the New Colonies to put themselves at the disposal of His Majesty’s troops in the late war was that the British Government, led by their known and proverbial sense of justice and equality, would, in the act of general settlement, have the position of the black races upon the land fully considered, and at the conclusion of the war the whole land would revert to the British Nation, when it would be a timely moment, they thought, for the English to show an act of sympathy towards those who had been despoiled of their land and liberties. Alas! This was not the case. The black races in these colonies feel today that their last state is worse than their first.”[24]

Much the same happened in the Cape. Coloured workers were unwilling to work for the Afrikaners, some of whom had gone to join the war, and all of whom were suspected of sympathy for the Boer cause.[25] “Why do you want to be called baas [boss],” they told their former employers. “Why are you back here? Why should we work for you?” Labourers were accused of being ‘work-shy’ and when popular discontent boiled over, British troops were called on to put down the unrest.[26]

With the war over, London had to deal with a restive black population while, at the same time, cutting a deal with the whites whom they had scarcely managed to conquer. The war had – as Rudyard Kipling memorably put it – taught the British ‘no end of a lesson’, but testing times lay ahead.[27]

[1] Andre Odendaal, op cit. 2012, p.263

[2] Thomas Pakenham, The Boer War, Abacus, 1992 (first published George Weidenfled & Nicholson, 1979) p. 402

[3] Andre Odendaal, op cit. 2012, p.264

[4] Sol T. Plaatje, Mafeking Diary; a Black Man’s View of a White Man’s War, edited by John Comaroff with Brian Willan and Andrew Reed, Meridor Books, Cambridge, 1973, p. 19-20

[5] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 5

[6] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 18

[7] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 18

[8] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 22

[9] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 47

[10] Andre Odendaal, op cit. 2012, p.265

[11] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 120-141

[12] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 93

[13] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 94

[14] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 97

[15] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 99

[16] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 98

[17] Thomas Pakenham, The Boer War, Abacus, 1992 (first published George Weidenfled & Nicholson, 1979) p. 572

[18] Stockwell Kessler thesis, quoted in Marika Sherwood, Origins of Pan-Africanism: Henry Sylvester Williams, Africa, and the African Diaspora, Routledge, Abingdon, 2011, p. 136

[19] Dennis Judd and Keith Surridge, The Boer War, John Murray, London, 2002, p. 234

[20] Dennis Judd and Keith Surridge, p. 235

[21] Thomas Pakenham, The Boer War, Abacus, 1992 (first published George Weidenfled & Nicholson, 1979) p. 573

[22] David E Torrance, The Strange Death of the Liberal Empire; Lord Selborne in

South Africa, Liverpool University Press, 1996, p. 102

[23] Martin Meredith, Diamonds, Gold and War, The Making of South Africa, Simon and Schuster, London, 2007, p. 494

[24] Martin Meredith, op cit. p. 494-5

[25] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 170-171

[26] Bill Nasson, Abraham Esau’s War: A black South African in the Cape, 1899-1902, African Studies Series, 68, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991, p. 181

[27] Rudyard Kilping, “The Lesson”. http://www.poetryloverspage.com/poets/kipling/lesson.html

Interesting article. You can read mine too on henrileriche.com

Two facts worth mentioning. New research of names by a well known historian in Bloemfontein found the figures of the white concentration camps to be 34 000.

Also the barbarity and rapes by Africans should not be excluded, especially mass rapes happening during the time when women were left on farms while the men fought. And the rapes included those done by British and Commonwealth soldiers. So this anger, had effects in other ways when Boers found Africans working for the British.

Brilliant! Well written!! Insightful – NO – RIVETING!! Im a fan!!